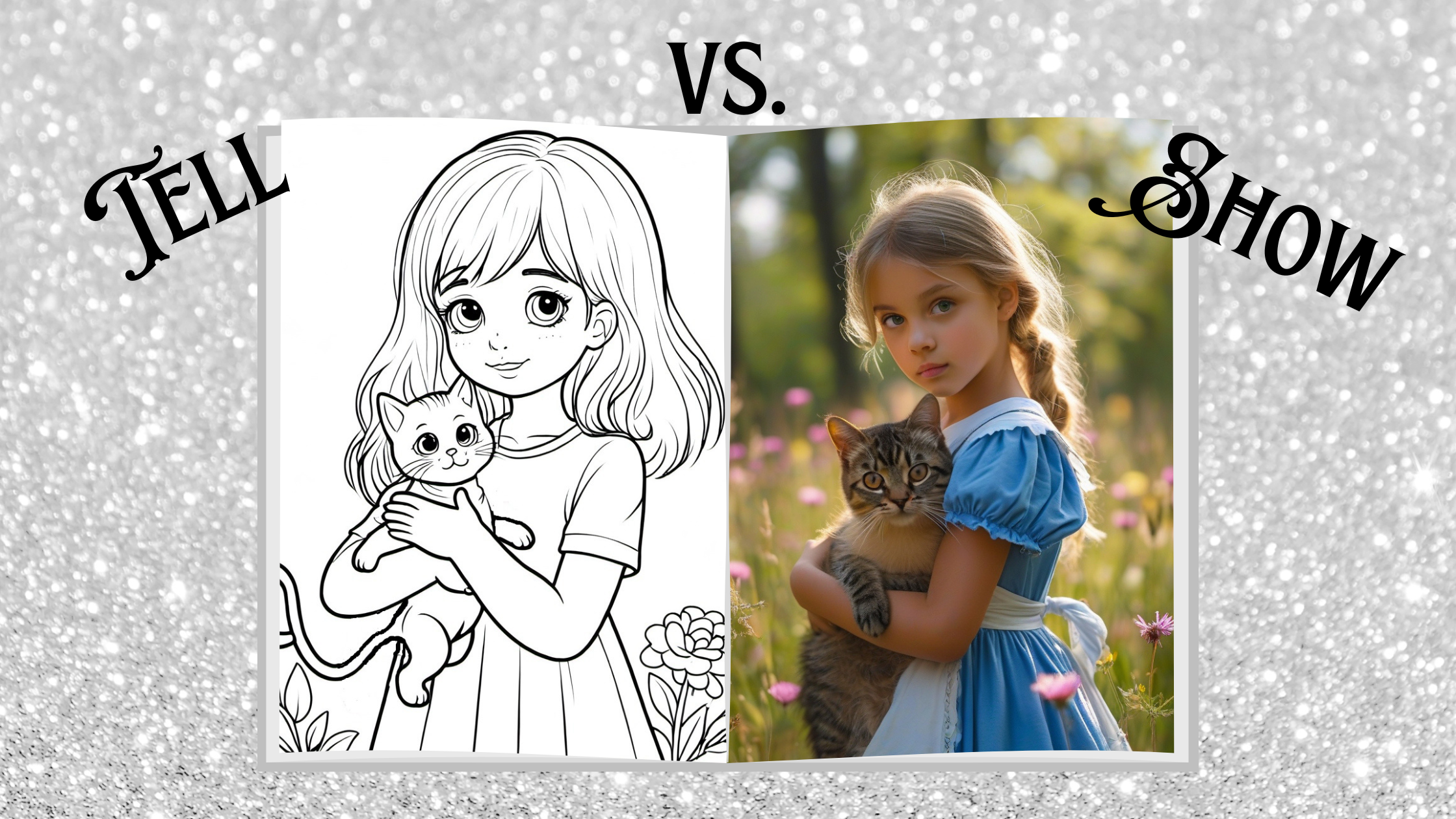

The Art of Writing Scenes That Show, Not Tell

We’ve all heard it: “Show, don’t tell.” But what does that actually mean when you’re staring down a blank page or slogging through a scene that feels… flat? If you’ve ever felt like your writing is more summary than story, or if you’re worried your characters are just talking heads in a white void, you’re not alone. Crafting scenes that pull your readers in and make them feel like they’re right there—that’s the real magic. And spoiler: it’s not about fancy words or dramatic monologues. It’s about immersion, and it starts with showing instead of telling. Let’s unpack what that really looks like.

Why “Show, Don’t Tell” Matters (and When to Break the Rule)

We’ve all had that moment where we’re told to “show, not tell”—maybe in a critique group, a writing workshop, or in the margin of a manuscript with a big ol’ red pen. But let’s be honest: that phrase can feel frustratingly vague. The good news? It’s not about writing “fancy” or being overly descriptive. It’s about giving your readers an experience. Showing invites them to see, hear, feel, and think with the characters. It creates intimacy. Immersion. That unputdownable quality we all crave. So let’s break it down, and also discuss when it’s totally okay to tell.

Emotions: Let the Reader Feel It

Telling: She was scared.

Okay, clear enough. But it keeps the reader at arm’s length. It’s like someone reporting what happened, rather than living it.

Showing:

Her fingers trembled as she fumbled with the lock. The hallway behind her stretched too quiet, too still. A bead of sweat slipped down her spine. She didn’t dare look back.

Here, the fear is layered. We’ve got physical responses (trembling fingers, sweat), environmental tension (quiet hallway), and a behavioral clue (not looking back). All of these together allow the reader to step into her shoes.

Writing Tip: If you’re unsure how to “show” an emotion, try this: close your eyes and imagine your character is in a movie. What’s the camera focused on? Their clenched jaw? That flicker in their eyes? Zoom in on the physical or behavioral signs. Let the reader interpret the emotion, rather than announcing it like a headline.

Extra Depth: Emotions aren’t always loud. Show the quiet panic, the held-in grief, the restrained joy. A character blinking too fast or holding a cup just a second too long? That’s gold.

Setting: Build the World Brick by Brick

Telling: The cabin was old and creepy.

It gets the job done, sure. But it doesn’t transport the reader.

Showing:

The floorboards groaned under each step, dust swirling in the slats of moonlight that filtered through cracked shutters. A cobweb brushed her cheek, and she bit back a yelp. The fireplace was choked with ash, its hearth blackened by decades of forgotten winters.

Now we’ve got atmosphere. Not just “old and creepy,” but tangible age, disrepair, and a sense of long-forgotten presence. We’re working with sound, touch, light, and even smell.

Writing Tip: The more senses you include (sparingly!), the deeper the immersion. You don’t need to overload every sentence with description, but anchoring your scene in 1–2 vivid, specific details can do more than a whole paragraph of vague imagery.

Bonus Note: Choose unusual details that evoke emotion. “Cracked shutters” hit differently than just “broken windows.” One feels rustic and eerie; the other just feels broken.

Action: Make It Cinematic

Telling: He was angry and stormed out.

It’s quick, but it skips the emotion’s weight. What kind of angry was it—cold? explosive? wounded?

Showing:

He shoved his chair back so hard it toppled. His jaw clenched. Hands fisted. He snatched his coat from the hook, knocked over a lamp on the way out, and slammed the door so hard the wall trembled.

Now we’re showing what anger looks like when it boils over. The violence is in the little moments, such as toppling the chair, slamming the door, or even the unintentional damage (like the lamp). The body language reinforces the emotion, making it feel visceral.

Writing Tip: Actions often speak louder than adjectives. Try writing the scene without naming the emotion, just show how it manifests in the body, voice, or surroundings. Then read it back. Odds are, the reader will still know exactly what the character is feeling.

Optional Exercise: Take a scene where your character feels a big emotion (grief, rage, joy, shame). Write it twice, once by “telling” the emotion and once by describing what they do, say, or notice. Compare the effect.

Dialogue: What’s Said and Unsaid

Telling: She was nervous about the interview.

Showing through dialogue:

“I’ve read every question they might ask,” she said, smoothing her skirt for the fifth time.

“You’ll be fine.”

“What if I freeze? What if I forget my name? I should’ve worn the blue blouse. It makes me look smarter, right?”

Here we see her inner chaos spilling out. It’s not just the words. Her fidgeting, repetition, and spiraling thoughts all convey anxiety. You don’t have to say she’s nervous. We feel it in the rhythm and content of her dialogue.

Writing Tip: Dialogue is gold when it comes to showing, but it’s not just about what your character says. It’s about how they say it, what they don’t say, and how others respond. Use interruptions, hesitations, and body language layered into the lines to say more with less.

Pro Move: Internal dialogue counts, too. If your character’s thoughts spiral, contradict, or loop, readers will sense their emotional state without a single label.

Deepening the Scene: Sensory Detail, Body Language, and Subtext

Once you’ve started “showing” instead of “telling,” the next step is to layer in the kind of depth that makes your scenes memorable. Now your reader doesn’t just see what’s happening, they feel it in their bones. Let’s talk about how sensory detail, body language, and subtext all work together to create that immersive, cinematic quality in your writing.

Sensory Detail: The Fastest Way Into a Scene

When in doubt, go sensory. Not purple-prose overload, just add a few precise, vivid touches that bring your world into focus.

Bad telling: It was a hot day.

Better showing: The air shimmered over the asphalt, and sweat pooled in the crook of her elbows before she’d even reached the car.

Now we’re not just hearing it’s hot, we’re feeling it. You can practically smell the heat rising from the pavement.

Writing Tip: Aim for specific, tactile detail. Instead of “the flowers smelled nice,” try “honeysuckle clung to the porch rail, sweet and sticky in the back of her throat.” The more unexpected the image, the more it sticks.

Quick Exercise: Describe a place using at least three senses, but leave out sight. It’ll force you to reach for smells, textures, and sounds you might otherwise skip.

Common Pitfall: Don’t describe everything. Readers want a spotlight, not a full security camera feed. Highlight the emotional beats with sensory anchors, such as the sharp smell of rubbing alcohol before bad news, or the itchy tag on a dress that makes a character feel out of place.

Body Language: The Dialogue Behind the Dialogue

Sometimes the most honest part of a scene is what a character’s body is doing while their mouth is saying something totally different.

Telling: He felt awkward at the party.

Showing: He hovered near the snack table, picking at chips he didn’t want, his eyes flicking toward the door every few seconds.

Now we see the discomfort, right? He’s not standing in the center of the room, laughing. He’s clinging to a safe corner, hoping to escape.

Writing Tip: People leak emotion through motion. Fidgeting, posture, repetitive gestures, crossed arms, tapping feet, these are all mini-signals that clue your reader in on what’s really going on. And when they contradict the dialogue? That’s where things get juicy.

Example:

Dialogue: “I’m not mad.”

Body language: She doesn’t look up. Her knuckles are white around the wine glass. One foot is already pointed toward the hallway.

Bonus Layer: Characters don’t always know what they’re revealing. Use body language to hint at things your character hasn’t admitted to themselves yet, such as fear, attraction, or distrust. This is great for slow-burn tension.

Subtext: The Words Beneath the Words

Ah, yes, the unsung hero of great storytelling. Subtext is the art of letting your characters not say what they mean and letting your reader pick up the thread.

Telling: They were in love, but afraid to admit it.

Showing through subtext:

He reached for her hand. “Your fingers are freezing.”

“It’s the wind,” she said, but didn’t pull away.

Neither of them looked at the other.

There’s no mention of love. Or fear. But it’s all right there, in the hesitation, the touch, the silence.

Writing Tip: Subtext lives in what’s unsaid, in pauses, looks, half-finished sentences. Let your readers read between the lines. Trust that they’re smart enough to get it.

Exercise: Try writing a scene where two characters are arguing about one thing on the surface, but underneath, they’re really hurt about something else entirely. Don’t let them say what it’s really about. Let the emotion leak through tone, pacing, and word choice.

Real Talk: Writing subtext well takes practice, but when you nail it? Chef’s kiss. Your characters will suddenly feel real, complex, and alive.

Shaping the Experience: Pacing, Scene Focus, and Inner Monologue

You’ve got your sensory detail and subtext working hard, but now it’s time to fine-tune how your reader moves through a scene. Do they feel breathless, slow-burning dread, or quiet reflection? That’s where pacing, focus, and inner thought come in. These aren’t just sentence-level tricks. They’re how you control time, tension, and emotional intensity in your story.

Pacing: When to Slow Down, and When to Cut to the Chase

One of the sneakiest ways to “show” is by controlling how fast (or slow) the reader moves through the moment.

Fast pacing (used for action or tension):

He ran. Gravel flew under his boots. The trees blurred past. A shot cracked behind him. He didn’t look back.

Short sentences. Punchy rhythm. It mimics the character’s adrenaline. The reader can’t help but race through it.

Slow pacing (used for reflection, dread, or intense emotion):

She reached for the door. Her fingers hovered just an inch away from the knob. One deep breath. Another. The smell of old wood, the faint scratch of wind outside. Was he in there? Was she really going to do this?

We’re drawing out each micro-moment because it matters. Slowing down shows the internal weight of the action without telling us “She was nervous.”

Writing Tip: Ask yourself, “Is this a moment the character would notice?” If yes, zoom in. If no, move fast. That’s how pacing helps prioritize what to show.

Pro Trick: Pacing is your secret weapon in thriller scenes and romantic ones. Anywhere stakes or vulnerability are high, a well-paced beat can make a reader forget to breathe.

Scene Focus: Zoom In, Zoom Out

Telling often happens when a scene tries to do too much. Showing works best when you know what the scene is really about and then zoom in on that.

Vague scene: They got into a fight about her working too much. He left angry. She cried.

That’s basically a summary. The reader’s kept at arm’s length.

Now let’s zoom in:

“You’re never here.” His voice was low but sharp. “You come home, eat in silence, then vanish into that damn office.”

She stared at the uneaten pasta between them. “I’m trying to build something.”

He shoved his chair back. “Yeah. And I’m not part of it.”

The door slammed. Her fork never made it to her mouth.

Same emotional content, but now it’s alive. The scene doesn’t need a backstory or emotional explanation. The words, silences, and details do the work.

Writing Tip: Don’t try to summarize a fight, kiss, realization, or turning point. Show the moment it happens. What’s said, what’s not, and what’s noticed.

Bonus Insight: One powerful detail can carry a ton of emotional weight. That uneaten pasta? It does more than a whole paragraph of “she felt sad.”

Inner Monologue: The Character’s Unfiltered Truth

Characters don’t always speak their mind, but their inner thoughts? That’s where the real juice is. Inner monologue is the best way to reveal a character’s doubts, desires, and decisions as they unfold.

Telling: He didn’t trust her.

Showing via inner thought:

She smiled too easily. Said all the right things. But something about her felt… off. Like she was playing a part, waiting for a cue. He kept one hand near his pocketknife.

Now we’re inside his head. His suspicion is more than just a label. It’s a lens through which he sees her, and it changes his behavior.

Writing Tip: Inner monologue works best when it’s in the character’s voice. Don’t write it like a narrator. Write it like them. Sarcastic? Paranoid? Romantic? That flavor will help the emotional truth land harder.

Example:

Oh great. A locked door. Classic. What is this, a horror movie? Cool. Guess I’m about to die.

That’s not just thought. It’s tone, mood, and voice rolled into one.

Quick Exercise: Take a moment from your story where something big happens—someone leaves, someone kisses, someone lies. Now write the inner monologue running underneath it. What’s your character thinking that they don’t say out loud?

Frequently Asked Questions: Show, Don’t Tell Edition

What exactly is the difference between showing and telling?

Great question!

Telling is when you inform the reader of something, like “she was sad” or “the night was cold.” Showing is when you illustrate it through actions, sensory details, dialogue, or behavior, as in “She wrapped her arms around her knees and stared at the rain tapping the window.” Showing lets readers draw their own conclusions and feel more immersed in the moment.

Is it ever okay to tell instead of show?

Absolutely.

Not every sentence needs to be a cinematic masterpiece. Sometimes you just need to say “Three weeks passed,” or “They packed up and left.” Telling can help with pacing, transitions, or summarizing unimportant events. The trick is knowing when to tell and when to slow down and show the stuff that matters emotionally.

I tend to over-describe everything. How can I avoid that?

First of all, you’re not alone.

Over-showing is totally a thing, and it can bog down the pace. The key is balance. Focus on the emotional heart of the scene. What’s the most important feeling or decision in this moment? Zoom in there. Not every object on the table needs a paragraph. Just pick 1–2 strong details that support the mood or reveal something about your character.

Can I “show” in a first-person or third-person POV?

Yes, yes, and yes!

Showing works in any point of view. In first-person, you can use inner monologue and personal perception to bring the reader closer. In third-person, you can zoom in on body language, behavior, and environmental cues. Showing is more about how you present information than who is doing the telling.

What are some quick tricks to check if I’m telling too much?

Here are a few handy tests:

- Do you use emotional labels a lot? (e.g., “She was angry,” “He felt guilty”) Try rewriting those lines with action or sensory cues.

- Are your characters just saying exactly what they feel in dialogue? Try layering in subtext or body language.

- Are you summarizing big scenes (like fights, breakups, or plot twists) in a sentence or two? Consider expanding them into real-time action.

Is “show, don’t tell” just for fiction writers?

Nope!

While it’s most commonly used in fiction, showing is also a powerful tool in memoir, creative nonfiction, screenwriting, and even blogging. Anytime you want your reader to feel something instead of just reading information, showing can help make your writing more vivid and impactful.

Final Thoughts on The Art of Writing Scenes That Show, Not Tell

If there’s one takeaway from all this, it’s that showing isn’t about stuffing your scenes with description. It’s about creating connection. When you show instead of tell, you’re giving your reader front-row seats to the emotional heart of your story. You’re letting them feel the tension, the ache, the joy, the fear without needing to spell it out.

But here’s the truth: you don’t have to get it perfect in the first draft. (Spoiler: nobody does.) The magic of showing often comes in revision. So don’t stress if your draft is full of telling. That just means you’ve got a solid foundation. Now you get to go back and sprinkle in those immersive details, tweak the pacing, and let your characters speak with their actions, not just their words.

Practice. Play. Be bold. Try things. And most of all, trust your reader. They’re smarter than you think, and they want to feel your story as much as read it.

Now go write some scenes that make your readers forget where they are. You’ve got this.