Writing a Better Antagonist: Redemption, Regret, and Moral Gray

Every writer loves a good villain. The real kind, the one who makes readers grit their teeth, whisper “oh no,” and flip pages faster. But here’s the uncomfortable truth we don’t talk about enough: your Antagonist probably deserves a redemption arc… sort of.

Not a full halo-and-harp redemption. Not a sudden personality transplant. But a moment, a crack, that lets the reader see who they could have been. Why? Because flat villains feel like cardboard cutouts, while layered antagonists feel like people.

And people are terrifying.

Readers want villains who feel real. A mustache-twirling Antagonist with no depth might work in a cartoon, but in fiction meant to linger, readers want more. They want contradictions. They want moments that make them uncomfortable for sympathizing.

Why? Because complexity mirrors real life.

No one wakes up thinking, “Today I will be the villain.” People justify, rationalize, and believe they’re right. When your Antagonist shows signs of internal conflict, readers lean in. They start asking questions. And once readers ask questions, they’re hooked.

Redemption Arc vs. Humanization: Know the Difference

Here’s the big misunderstanding: a redemption arc is not the same as forgiveness.

This is where writers often panic. They worry that if they make the Antagonist too human, readers will think the story is excusing them. But that only happens when the line between redemption and humanization gets blurred.

Humanizing your Antagonist doesn’t mean absolving them. It means acknowledging their humanity. There’s a massive difference.

Let’s break it down in plain terms:

- Redemption means change plus accountability.

- Humanization means understanding without approval.

Those two things can overlap, but they don’t have to.

What Humanization Looks Like

Humanization is when you let the reader see the Antagonist as a person, not just a problem. You show pieces of their inner life without asking anyone to forgive them.

For example:

- The Antagonist visits their mother in a nursing home every week, even though they’re ruthless everywhere else.

- They hesitate before giving an order that will hurt someone, even if they give it anyway.

- They genuinely love their child, their sibling, or even a pet.

None of this erases the harm they cause. It simply tells the reader, “This is a human being who makes choices, terrible ones included.”

Think of it like this: you can understand why someone became cruel without agreeing that cruelty was justified.

What Redemption Looks Like

Redemption, on the other hand, requires action and consequence. A truly redeemed Antagonist doesn’t just feel bad. They do something different, and it costs them.

For example:

- They confess to a crime knowing it will destroy their power.

- They protect someone they would’ve once sacrificed, even if it leads to their own downfall.

- They undo harm where possible, knowing it won’t erase the past.

Redemption isn’t about saying “sorry.” It’s about making a different choice when it matters most.

Why Confusing the Two Weakens Stories

When writers confuse humanization with redemption, they often fall into one of two traps:

- The Antagonist gets sympathy without consequences.

- The story rushes forgiveness before change feels earned.

Readers feel that disconnect immediately. They might understand the Antagonist, but they won’t believe the story if accountability never shows up. You can absolutely show your Antagonist’s pain, love, or regret without erasing the damage they’ve done.

Think of it like understanding why a house burned down. You might learn about faulty wiring, bad weather, or neglect. That knowledge gives context, but it doesn’t magically rebuild the house or bring back what was lost. The fire still destroyed everything inside.

And that’s the balance you’re aiming for: clarity without excuses, empathy without erasure, and depth without absolution.

That’s where truly unforgettable Antagonists live.

The Antagonist Is the Hero of Their Own Story

If you only remember one thing from this article, make it this: Your Antagonist believes they are right.

They may believe they’re saving someone. Fixing a broken system. Protecting themselves. Even acting out of love. That belief shapes their choices—and makes them dangerous.

Ask yourself:

- What does your Antagonist want more than anything?

- What fear drives them?

- What line do they believe they’ll never cross (until they do)?

When you answer these honestly, redemption—or its failure—starts to feel earned.

Backstory Is Not an Excuse (And Shouldn’t Be)

Yes, your Antagonist may have trauma.

Loss.

Abuse.

Poverty.

Betrayal.

That explains behavior, but it does not excuse it.

This is where writers often mean well and accidentally sabotage their own story. They pour heart and care into an Antagonist’s past, only to cross an invisible line where explanation turns into justification.

Readers feel that shift immediately.

Cause vs. Justification: Readers Know the Difference

Here’s the simple truth: readers are smarter than we give them credit for.

They understand that experiences shape people. What they won’t accept is being told, implicitly or explicitly, that suffering grants permission to harm others.

For example:

- An Antagonist who grew up abused might struggle with control. That explains why they crave power.

- It does not excuse manipulating, terrorizing, or destroying others to get it.

When a story treats trauma as a free pass, readers disengage. They don’t feel compassion. They feel handled.

How to Use Backstory the Right Way

Backstory should add weight, not remove it.

A painful past makes an Antagonist’s choices heavier because it shows they know what pain feels like and choose to inflict it anyway. That tension is powerful.

Here’s what effective backstory does:

- It deepens motivation

- It clarifies emotional stakes

- It makes choices more tragic, not cleaner

For example:

- An Antagonist abandoned as a child may fear being powerless, but choosing to abandon others in return becomes a conscious, devastating echo.

- Someone who survived poverty might hoard resources, but doing so at the cost of lives remains a moral failure.

The backstory doesn’t soften the act. It sharpens it.

Let Consequences Still Matter

One of the biggest mistakes writers make is letting backstory erase consequences.

If everyone forgives the Antagonist because “they’ve been through a lot,” the story loses credibility. Pain doesn’t dissolve accountability. It increases the expectation that the character knows better.

You don’t need to punish your Antagonist endlessly. But actions must still matter. Damage must still exist.

Context, Not a Pardon

Think of backstory as context, not a pardon.

It’s the reason the road bent the way it did, not a sign that the destination doesn’t matter. Understanding how someone arrived at a choice doesn’t mean that choice stops being wrong.

When you treat backstory this way, you respect both your characters and your readers. And you create Antagonists who feel real, tragic, and unsettling—without ever asking the audience to excuse the inexcusable.

That balance?

That’s where the story gets its teeth.

The Almost Choice: Where Moral Gray Does Its Best Work

One of the most powerful tools you have as a writer is the almost redemption—the moment when your Antagonist could choose differently…and doesn’t.

This isn’t a grand turning point with trumpets and speeches. It’s quieter than that. Smaller. And far more devastating.

It’s the pause before the order is given.

The hand that hovers before pulling the trigger.

The truth that almost gets spoken.

That hesitation, the flicker of doubt, is where moral gray lives.

Why the Almost Choice Hurts So Good

When your Antagonist stands at the crossroads and almost turns back, readers see something crucial: redemption was possible. This character wasn’t born evil. They aren’t a force of nature. They are a person making a choice.

And when they choose wrong anyway, the tragedy deepens.

For example:

- An Antagonist has the chance to let someone escape. They even unlock the door before locking it again and telling themselves it’s “necessary.”

- They consider sparing a rival’s family, knowing the cycle could end here, but decide that fear is more useful than mercy.

- They almost confess a lie that’s destroying everything, until they realize telling the truth would cost them power.

Nothing forces them to choose wrong. And that’s what makes it hurt.

Moral Gray Is Where Characters Feel Real

Clean morality is simple. Gray morality is haunting.

An Antagonist who only does evil is predictable. An Antagonist who does good things for selfish reasons, or terrible things for understandable ones, creates emotional conflict in the reader. And conflict keeps stories alive.

Let your Antagonist exist in contradiction:

- Love deeply but not universally

- Protect fiercely while choosing who deserves safety

- Regret privately but never enough to change

For example:

- They save one child because they remind them of someone they lost, while condemning others without hesitation.

- They show mercy not because it’s right, but instead because it soothes their conscience.

- They feel genuine remorse at night, then make the same choice again in the morning.

These moments don’t weaken your Antagonist. They sharpen them.

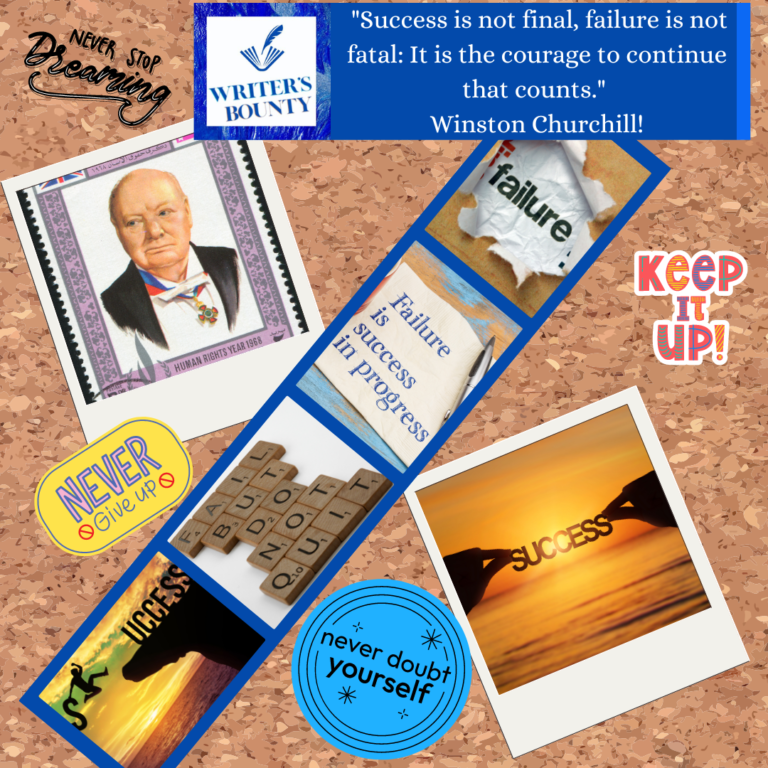

Why Failure Is Often More Powerful Than Redemption

The almost choice paired with moral gray creates realism. Most people don’t fail because they’re incapable of good. They fail because good is harder, riskier, and more costly than staying the same.

When an Antagonist chooses wrong after considering right, the reader understands them more and fears them more. They didn’t fall because they couldn’t climb. They fell because they chose not to.

That’s the kind of Antagonist that lingers. The one readers argue about, feel conflicted over, and remember long after the story ends. Because in that almost moment, we see ourselves. And we realize how close anyone can come to becoming the villain of their own story.

Common Redemption Arc Mistakes Writers Make

Redemption arcs are powerful—but they’re also fragile. A single misstep can turn an emotionally rich storyline into something that feels rushed, manipulative, or downright unbelievable.

If you want your Antagonist’s arc to land, avoid these common traps.

Sudden Personality Flips

This is the big one.

If your Antagonist goes from ruthless to selfless overnight, readers won’t feel moved. They’ll feel whiplash. Real change is slow, uneven, and uncomfortable. People don’t wake up cured of their worst instincts just because the plot needs them to.

For example:

- A character who has been manipulative for the entire story doesn’t suddenly become honest because they had one heartfelt conversation.

- A violent Antagonist doesn’t become gentle without struggling against those habits.

Change should feel like a process, not a switch.

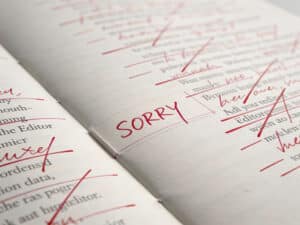

Apologies Without Action

“I’m sorry” is not redemption. Words are easy. Action is expensive.

If your Antagonist apologizes but doesn’t do anything differently, readers see right through it. Regret without behavior change is just guilt, and guilt alone doesn’t fix damage.

A meaningful arc shows:

- Changed decisions

- Sacrifices made

- Risk taken to do the right thing

Without action, apologies are just noise.

Forgiveness Without Consequences

This one breaks trust with the reader fast.

If everyone forgives the Antagonist simply because they tried, or because the story wants a neat ending, it feels unearned. Harm doesn’t vanish because someone feels bad about it.

Consequences don’t have to be extreme, but they must exist:

- Lost relationships

- Broken trust

- Reduced power or freedom

Forgiveness that costs nothing feels hollow. Redemption that hurts feels real.

Redemption Used as a Shortcut to Likability

This is where writers get tempted to “fix” a villain instead of developing them.

A redemption arc is not a personality makeover. It shouldn’t be used to suddenly make the Antagonist charming, funny, or heroic just so readers like them more.

Readers don’t need to like your Antagonist. They need to believe them.

Some of the most compelling redeemed (or almost-redeemed) characters are still difficult, abrasive, or morally complicated. And that’s okay.

Why Readers Are Less Forgiving Than Characters

Here’s the truth that stings a little:

Readers will forgive a cruel Antagonist before they forgive lazy writing.

They’ll accept dark choices, moral failure, and even refusal of redemption, as long as it feels honest and earned. What they won’t accept is being rushed, emotionally manipulated, or asked to ignore logic for the sake of a tidy ending.

If you respect the process, the messiness, and the cost of change, readers will follow you anywhere, even into uncomfortable territory.

And honestly? That’s where the best stories live.

Final Thoughts on Antagonist Redemption: Possibility, Not Permission

Your Antagonist doesn’t need saving. They need depth. A redemption arc, or the denial of one, is about showing what was possible, who they might have been, and what choice they couldn’t make.

Whether you decide to truly redeem your Antagonist or just want to include a humanizing act, give your Antagonist that moment at the crossroads. Whether they step forward or walk away, your story will be stronger for it. If you’re writing villains who linger in readers’ minds, you’re doing it right. And if your Antagonist almost changes but doesn’t? That ache you feel is exactly what your story needs.

For more information on character building, check out “Building Character Backstories: Tips & Tricks for Rich Histories.”